A-i-R Journal—Micheal Two Bulls

Aaniin! My name is Neebinnaukzhik Southall. I am a member of the Chippewas of Rama First Nation and a student at the Institute of American Indian Arts. IAIA’s Artist-in-Residence programs bring Native artists from a range of cultures and practices to the IAIA campus, benefiting artists, students, and the wider Santa Fe community. I really love the A-i-R programs. I saw their beginnings through my close friend, Jonathan Loretto, who was one of the first two artists in residence. His positive experiences prompted him to return to IAIA as a student, and in turn, he recruited me. I am now working my way towards a Native American art history certificate.

Jonathan Loretto and Lara Evans in 2015, photograph by Neebinnaukzhik Southall

The A-i-R events offered to the public and IAIA students are an incredible resource. (Plus, free public welcome dinners!) For me, recent highlights include participating in IAIA alumnus Leanne Campbell’s Plateau basket making workshop—since graduation, she’s taught the art form to many other people in her community, helping to revitalize and maintain the practice. While I was taking an art history class last semester, we read about Erica Lord, and then I actually got to see her present! For a favorite memory, my parents were visiting and I was able to take my mother to Wanesia Misquadace’s birchbark biting workshop. I cannot emphasize enough how meaningful it was to be able to engage with our Anishinaabe culture with other Anishinaabe people here in Santa Fe.

Now, I’m happy to be interacting with the A-i-R programs in a new way, as a blogger covering the artists themselves, alongside fellow student Angelica Gallegos.

My mother at Wanesia Misquadace’s birch bark biting workshop, photograph by Neebinnaukzhik Southall

Micheal Two Bulls is an Oglala Lakota multimedia artist, who is notable for his multilayered compositions incorporating digital work, photography, drawing, painting, and a variety of print-making methods. Two Bulls returned to the IAIA campus as an alumnus, where he originally focused on printmaking. Meeting him was particularly exciting, as he is the artist behind a suicide prevention poster commissioned by the Lakota Voice Project, which I previously purchased from his spouse Angel Two Bulls at an IAIA event. As a graphic designer myself, I was drawn to his composition and usage of imagery to create a culturally relevant design to reach Lakota people.

Micheal Two Bulls is using his time at IAIA to develop work for Takuwe, an upcoming traveling exhibition in South Dakota reacting to and raising awareness of the impact of the 1890 Wounded Knee massacre of the Lakota, organized by Dr. Craig Howe (Oglala Lakota) of the Center for American Indian Research and Native Studies. “He’s curating a show about the Wounded Knee massacre—the events that led up to it, during, and after,” explained Two Bulls. Each of the twenty-nine participating visual artists were assigned a section. Two Bulls’s work will deal with the aftermath.

Part of the work is processing the event. He had several books from the IAIA library on a work table and made note of materials sent by Dr. Howe, who organized historical information and records into a timeline for the artists. “It’s a pretty powerful show, I think. It’s a kind of a hard subject to really tackle. I’ve kind of had a hard time—I’m still having a hard time with it,” admits Two Bulls. “You know what I mean—what to do, where to take it.”

Neebinnauk Southall (left) and Micheal Two Bulls (right), photograph by Jonathan Loretto

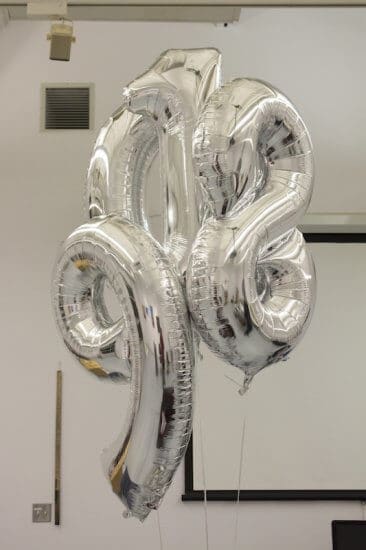

He had two pieces in progress—of these two, he would select one for inclusion in the show. When I met up with Two Bulls, he was working on the computer on a photo he had taken of balloons, arranged to spell the year 1890, which would be screen printed on one of the pieces. He noted that the intent wasn’t humor. “Why are they balloons? What’s the point of that? So the whole point is to kind of grab the viewer right away—this date is forever immortalized in Lakota history, even Native history in general,” said Two Bulls.

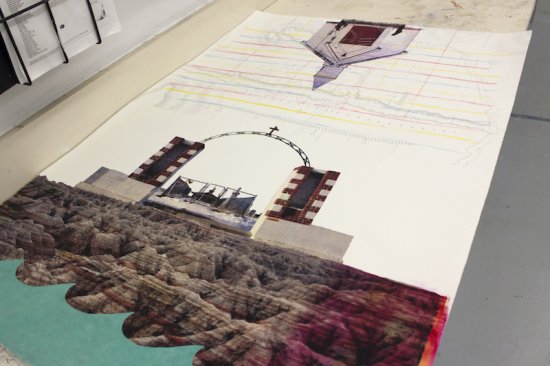

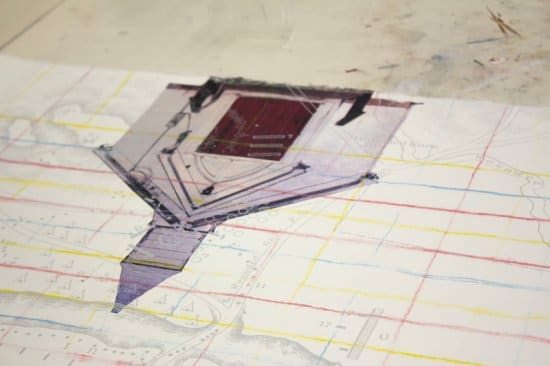

A foundational aspect of both works is a screen print incorporating three components: an upside down church at the top, a gravesite in the middle, and a landscape element grounding the bottom. He began the piece by taking photographs, which he prepared and printed in four layers of color at IAIA. “So before I came here, I went out and took these photographs. This is the entry way into the mass burial grounds, the site, I should say. And this is kind of like the terrain, the Badlands area. Upside down, this church is where they took all the dead and wounded into that church at that time.”

I was taken aback to learn that the church, still in usage, has visible blood stains from the incident on the original wood floor. I couldn’t understand why it would be left that way. Micheal’s descriptors for the area included “intense” and “surreal.” “So when I went there,” said Two Bulls, “I took the photos really quick, and left a tobacco offering.” He mentioned that one person with land near the massacre was attempting to sell land back to the tribe for millions of dollars.

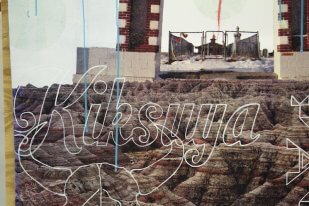

I learned that a magpie, painted in the corner of one of the compositions, is significant within Lakota culture. Two Bulls told me a story regarding the magpie: “Bisons kind of ruled the world, but the creator decided to have a race around the Black Hills, and whoever won, that would decide, you know, who was on top of the food chain. And the magpie has an important part of that story, where he rode on the bison’s back, you know, into the whole race, and he won the race.” Grasped in the magpie’s talons is a red line twisting across the page back to the grave site, achieved by pressing a string soaked with red ink unto the surface with a press. Towards the bottom of the piece, there was a word overlaid on the image, “Kiksuya,” which Two Bulls explained means “remember” in Lakota. Outlined in white, the imagery was echoed by a similarly outlined bison skull, as well as a geometric Lakota design. Two Bulls planned on adding an image of a DNA strand to the composition. His aim was to have every component in the piece be meaningful.

Micheal will participate in the Takuwe exhibition not only as one of the visual artists, but also as a musician, as one of the members of The Wake Singers. Toward the end of our interview, he asked me if I’d like to hear what he was working on, and of course I said yes. He was partway through a collaborative piece prominently featuring a cello. “Before I came here, I had my little cousin do all the cello tracks,” noted Michael. What he had so far was really cool.

Kiksuya, meaning remember, photograph by Neebinnaukzhik Southall

I asked Micheal what it was like returning to IAIA as a working artist. “Oh man, I’ve had fun, like, it’s cool because a lot of the teachers are inviting us to talk to the students,” Micheal related, remembering when he was on the other side of it. Much has changed since he graduated. “But it’s really cool. I mean, it’s grown so much for the better, you know.” He mentioned greater resources for students, such as a sophomore seminar touching on the business side of art. Back when he attended, there were just a few buildings, and “the library wasn’t built yet.” He’s had a lot of students drop by the studio, and appreciates the interaction. “Where my head’s at right now, it’s kind of heavy stuff. But you know, I mean, it’s the perfect place to do it—getting some feedback from students and teachers.” Several of his old school friends also now work on the campus.

We chatted about his other involvements and upcoming projects. He’ll be back in Santa Fe as a First Peoples Fund fellow, and is also a fellow for Dr. Howe’s organization, the Center for American Indian Research and Native Studies. Two Bulls noted differences between the developing arts scene in South Dakota and Santa Fe. For one, it’s a smaller community. “Up north, we kind of have to band together a little more closely,” stated Two Bulls. He will be participating in the Red Cloud Indian Art Show, entering its 50th anniversary this year. “So I’m making a big sculpture for it and everything,” revealed Two Bulls. “Angel is beading on the wings. So it should be cool.” Another show he’ll be participating in is Native POP: People of the Plains, where he has previously won awards. The show is organized in part by Mary Bordeaux and Peter Strong, who also run Racing Magpie, where Two Bulls shares studio space with other artists. (Fun fact: Wade Patton, one of the other artists in residence at IAIA, also works in the same space.)

Micheal and Angel (who is also involved with the Indigenous Film Festival) have one particular long-term vision—opening a small art school on the reservation. Over time, they’ve been gathering equipment toward this end, such as photo enlargers, a kiln, and soon, an etching press. I followed up with Micheal via email after our interview, and he elaborated on how the school would function as a resource for a highly creative community.

“In a recent impact study on the Pine Ridge reservation, 80% of families make their income through arts and craft. This study is affected by lack of jobs, tourism, a grassroots economy and deep rooted Lakota culture (which reflects through many forms of art). A lot of people have raw talent and dedication, and it’s important to nurture that. Angel and I thought of an art school of sorts where community members’ talents can be honed and that grassroots community could be grown.”

My impression of Micheal Two Bulls is that he is very grounded, made apparent by his gentle, approachable demeanor, the content of his work, and his community connections. It’s refreshing to see a person with so many creative skills remain humble. I enjoyed learning more about Two Bull’s work, and look forward to seeing what he does next.

For my next entry, I’ll be chatting with artist-in-resident Orlando Dugi, who has made a name for himself in fashion design. We’ll see you then!

Photographic Gallery

Neebinnaukzhik Southall is a member of the Chippewas of Rama First Nation. She is a graphic designer, a photographer, an artist, and a writer covering Native art and design. She graduated from Oregon State University with a Honors BFA in Applied Visual Arts in 2011, and is currently pursuing a Native American Art History certificate at the Institute of American Indian Arts. Visit Southall’s website, www.neebin.com, to learn more about her.