A-i-R Journal—Meghann O’Brien

Meghann O’Brien giving a talk in her studio at the Welcome Dinner and Studio Tours on April 12, 2018, photograph by Neebinnaukzhik Southall

When you first meet Meghann O’Brien, a Haida, Kwakwaka’wakw, and Irish weaver and designer who is notable for her fine Chilkat and Ravenstail weavings and other works, you can tell that she is an artist right away. At the April 12th Welcome Dinner and Studio Tours for the latest artists-in-residence, she wore weaving materials as hoop earrings, and had a delightfully voluminous red dress with a big bow around the neck. The overall effect made me think she could be a heroine in a Hayao Miyazaki animation. Her commitment to her weaving is expressed in her body art—on the back of one of her hands, she has a black-lined tattoo of a motif found on some Ravenstail weavings, and she also has markings to denote weaving projects. When I met up with her for an interview, her shoes were two different colors, a vibrant orange-red and yellow, respectively.

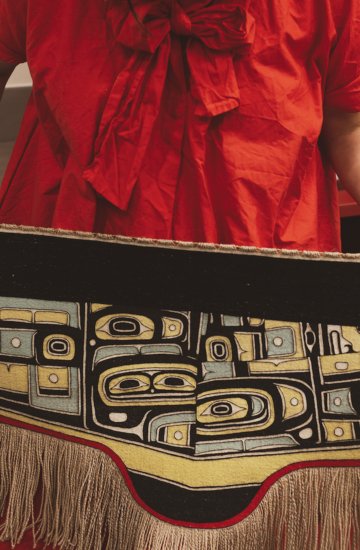

This is Meghann’s second time at IAIA. This year, she is participating through the Sunrise Springs IAIA Residency, a collaborative effort with the Sunrise Springs Spa Resort. Last year, she worked on a portion of a ceremonial apron. To give a sense of the time it takes to make one, she said she completed about a tenth of the piece in six weeks. I asked her about the differences in experience of last year compared to now. “I guess last year I was in the middle of a project I was really ready to finish too, so I was very focused on that,” Meghann noted. “So I put a lot of time in with that. But now, I am at the beginning of a new weaving project, which will take a few months of spinning before I am ready to hang it on the loom, so I have just slowly been getting back into that.” She also noticed that there was a growing interest in weaving, compared to her last time here. To create a Chilkat or Ravenstail robe represents many hours not only of weaving, but also preparing and spinning wool. She has spent a significant portion of her time during the residency engaging in this essential part of the process. “It’s so necessary, and it’s so beautiful, and it’s so over-looked,” she said. IAIA students got a taste of this aspect of weaving through a fiber spinning workshop.

“That was good…I mean, it was only two hours, so there wasn’t a whole lot you could accomplish with that. I think to do even a small piece, you’d need 5-7 days…just because the spinning, and then washing it, and drying—letting it dry—and then hanging it on the loom, and then going through learning some of the motions of how to do your stitches and the patterns. So that wasn’t really possible to share. But I recommended that…just with the spinning, it’s kind of a good introduction—kind of get your feet wet. And I mean, if somebody’s not willing to spend the time to spin their own wool, then it’s a good indicator that you’re not really that interested in learning more. But yeah, I just suggested that they make earrings, or make a bracelet or a necklace out of the work that they spun.”

This year’s residency also marks a greater shift into fashion. While Meghan has been focused on the creation of ceremonial garments in her weaving work, she’s also been exploring creating garments and accessories in a fashion context. Prior to coming to Santa Fe, she learned that she was going to participate in Indigenous Fashion Week Toronto. She brought fabric and then bought more with the funds from the residency materials budget. At Sunrise Springs, she has been focus-ing on her weaving, while at the campus in the Performing Arts Costume Shop, she’s been busy sewing.

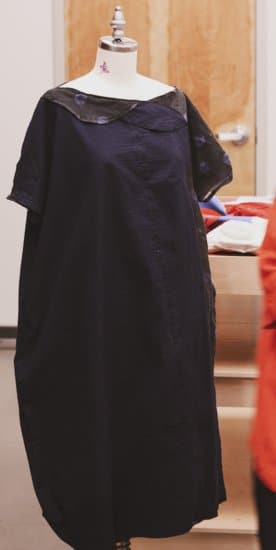

In the studio, she had strands wrapped around and pinned to a mannequin. During our conversation, she manipulated the strands and showed me how the material might become a sort of necklace, accented with a small weaving and incorporated as a structural and decorative element of a Western-style garment. I was fascinated by the way she can not only work in a framework of fine precision but also with such a freeness in her creative approach. “I’ve always loved and been obsessed with the warp,” revealed Meghann. “Just like having it, and looking at it, and the way that it moves, and the structure of it is really cool…Some of the pendants I’ve been doing lately, I love having that part of it getting more free, and seeing the form progress of how you can hang the warp, and play with it as almost like—sculptural or with a lot of structure—because once it’s off the loom—just being able to twist it, and bend it, and see it in different ways.” Another example of her willingness to play with materials was an in-process, oversized scarf on one of the work tables, pieced together with hand-dyed fabric bought from a quilting store.

I was intrigued to learn more about Meghann’s entry into the world of fashion. Her interest in weaving first began through her passion of harvesting wild food, and wanting baskets for berry-picking. The idea of functionality undergirds her interest in fashion as well, in the way that “fashion is a part of life today”. She lamented that Chilkat weavings, works which were originally meant to be worn and are viewed by her people as “having so much life and spirit,” are not used when they are kept in museum cases. This is part of her motivation to bring aspects of these cultural forms into an “every-day context” through fashion. Last fall, Meghann was invited by the Ociciwan Contemporary Art Collective to participate in Western Canada Fashion Week as a designer. Her focus was on accessories, which she showcased on five outfits she sewed herself, in tandem with five “thrift store looks” from her personal wardrobe. (Meghann writes about the experience in a recent blog post on her website, sharing history and her personal philosophy. The article is filled with beautiful photographs—be sure to give it a read!)

Of the experience, Meghan says, “It was really amazing, because it gave me the opportunity to really explore something I had been thinking about for a long time and expand on it…I used to sew when I was a kid, like in high school, and my mom was sewing my whole time growing up, but I haven’t really been making clothes in a long time,” she revealed. Meghann compared her exposure and approach to fashion to master Haida artist Robert Davidson’s framework of creating through an understanding of a Northwest Coast formline visual vocabulary: “In a different way, I know that Robert Davidson talks about building a database almost of—I don’t think he uses “database”—but like, building this repository of forms—like exposure to art. And I think I’ve had a huge exposure to design in fashion throughout my entire life, because it’s just been an interest for so long, so it’s fun to dig into that. And I consider the clothing more like sketches, or like impressions of clothing, because they’re really not that technically perfect. And I’m not a tailor, or a dressmaker. I’m just kind of like, going to town with my sewing machine.” Prior to her experience with the Ociciwan Contemporary Art Collective, she had some other involvements. “I got invited to give a talk at the Museum of Anthropology during Vancouver Indigenous Fashion Week,” she said. “So at the time, I didn’t apply for anything or have anything to show other than my weavings. And that was a good stepping stone just to get my feet wet in that environment and those conversations.” Dene designer Sage Paul, a well-known advocate for Native art forms and founder of Indigenous Fashion Week Toronto, had also shared Meghann’s work through a booklet which she took during a trip to fashion weeks in Europe.

Meghann had two billowy garments on forms in the studio. I asked her what she had in mind when she’s making her clothing. She answered, “I have in mind functionality and comfort. So I love riding my bike, and I love harvesting food, so I want to be able to bend down and lift my legs…I think modesty is a cool thing that I’m attracted to, in terms of how the dress fits—but still flattering in a way—so a balance between modesty and femininity. Respect for the female form…I love touching, and being in, and working with really beautiful material and fibers.” She uses natural materials such as silks, linen, and cotton. “Mostly how I’ve made these things isn’t with a pattern. It’s nice to have the dress forms, because last year I just sewed it. They are basically all made to fit my own body, with room, I guess. That’s why I think of them as sketches.”

For Indigenous Fashion Week Toronto, she’ll be presenting her work in a runway show on May 31, including robes, aprons, earrings, necklaces, pendants, woven leggings, and her sewn clothing. She will also be giving a two-day, ten-hour Ravenstail weaving workshop, in which participants will create a miniature weaving in the form of a wearable medicine bag. Meghann mentioned that Gitxsan designer Yolanda Skelton of Sugiit Lukxs Designs is excited to take the work-shop with the intent of using weaving in her own work. Skelton creates regalia and tailored works incorporating figurative, appliquéd Northwest coast designs and will also be participating in the runway show. Meghann in turn is happy to share her knowledge with someone with a shared cultural heritage of Ravenstail weaving. Economic considerations impact the number of people who work in this ancestral art form. Meghann related that there is a very small market for large completed weavings. “There’s not a whole lot of people who do it as a profession, I guess, or as a career, but there is a number, and they’re still very small numbers, but there’s a few more people that work in their communities and [are] doing it for their families.”

A significant part of our conversation involved the discussion of navigating ethical and appropriate usage of cultural practices and imagery in new forms and contexts. Meghann herself had apprenticed under other weavers, and has been working on her own for a few years now.

“It’s interesting to start doing workshops that are short, because I always told myself that I didn’t want to do that. I said I didn’t want to contribute to the partial distribution of knowledge. I think there’s a lot of responsibility that comes with the knowledge of how to make these things…giving people the power to make them, but also to have respect for it, whereas giving all these techniques out and then people just having—just wanting to do anything they want with with them. Maybe—I mean, I’m starting to do stuff I want with them too, but maybe that’s not my decision to make.”

How does one mindfully take risks? Relating to the issues Meghann raised, I talked about my own considerations as an Ojibwe person, particularly the question of how Ojibwe artists utilize sacred imagery of powerful beings in a proper way, while also striving to perpetuate culture. “Yeah, it’s a big question,” Meghan sympathized.

“Like I struggle with it a lot myself, still. And yeah, basically feeling like I worked really hard for the last decade at the techniques, and being really respectful of what my teachers shared with me. And how to—yeah, how to take something, like essentially have a way of doing things and an art form that comes from a society that when it was intact, and now there’s been so much social disintegration, and things interfering with it that…I no longer have that whole community or societal structure intact. I’m in capitalism, you know? And how do you take something that is essentially transplanted out of a different era into today, and figure out what the right thing to do with it is?”

Meghann O’Brien manipulating strings on a mannequin—the form may become a necklace and may be incorporated into the structure of a garment, photograph by Neebinnaukzhik Southall

In her personal process, she questioned whether it was appropriate to combine her weaving with Western forms, and we discussed the history of inspiration and syncretism of materials and methods by Native artists. “I started doing this research and I started seeing all these examples of like, in, you know, the 1800s, of how our people have been influenced by Western clothing for so long,” she noted. “And there’s like—it’s nothing wrong with it at all, I don’t think. Like I saw a really cool Chilkat blanket that had been cut up and it was tailored into like—they matched the front—it was a vest—and it matched—the patterns, the faces all matched together, and it had the buttons. But it was fully tailored!” She further went on to share some history of her region: “Chiefs on the Northwest Coast used to love wearing or trading for the ships’ captain’s uniform and wearing those, with their Chilkat blanket in the background. It’s so cool.” We discussed how trade and the appeal of novelty has long been a part of Native histories. “If something came from somewhere else, and you could get your hands on it, it was such a status symbol, because nobody else had it,” Meghan said.

While exploring different ways of doing things, she rejects the idea of fast fashion, and mentioned associated problems such as poor quality and environmental irresponsibility. “I like the idea of finding a way from new ways to bring things forward into today that are beautiful, and have a beautiful history around them—and keeping that integrity of the work,” she said.

“Historically there’s a lot of prestige and respect around Chilkat weaving,” she discussed. “I’d love to see it way more than something super disposable—more something that could compete as a status symbol, or be like a new kind of status symbol, but not of wealth necessarily. Only that there’s just so much that goes into knowing what it is, and it has so much more to do with better things than gold and diamonds. It’s something that’s gentle on the earth, and not extractive, and not detrimental to the people involved in it. So that’s what I’ve been super excited about, like looking at our ancestors’ work that we did, more as—because the only place that I see it still happening, where people are wearing things that are made with that much quality, is in the world of haute couture, and I like to look at the things our ancestors made as that—like the fully beaded and custom-made to each person…But I think ours is way more powerful than haute couture, because it has meaning. It’s not pure aesthetic. It’s got context and relevance, and it’s about connection to each other, and the whole natural world, and supernatural world.”

With my Native American Art History I coursework in mind, I related a story from the Native North American Art textbook in which a Dene woman not only survived alone, but also made decorated garments, which was presented in the cultural context of the North of dressing for the beings around us (Berlo, Janet Catherine and Ruth B. Phillips. Native North American Art, 2nd ed., Oxford University Press, 2015, pp. 176-177). At this, Meghann happily mentioned her own berry picking outfits that she wears “that match the berries.” “There’s one that I’ve got—and it’s navy blue and red and it’s like blueberries and huckleberries,” Meghann shared. She noted the idea of “dressing like your medicine,” and went on to say, “I love the idea that you’re in the presence of an old growth forest and I like to think that it sees you, you know. Be well dressed.”

Next year, Meghann O’Brien will again bring beautiful Northwest Coast woven forms to the Southwest as the School for Advanced Research’s prestigious 2019 Eric and Barbara Dobkin Native Artist Fellow. She’ll be in residence from March 1—May 31, 2019. Be sure to mark your calendars, and keep updated on her work through her website, Jaad Kuujus.

Neebinnaukzhik Southall is a member of the Chippewas of Rama First Nation. She is a graphic designer, a photographer, an artist, and a writer covering Native art and design. She graduated from Oregon State University with a Honors BFA in Applied Visual Arts in 2011, and is currently pursuing a Native American Art History certificate at the Institute of American Indian Arts. Visit Southall’s website, www.neebin.com, to learn more about her.